An Introduction to Positional and Structural Encodings for Graph Neural Networks

Writen by Patrick Soga, 10th December 2023

There has been a recent surge of interest within the graph neural network (GNN) com-munity regarding positional and structural encodings (PSEs) for graph data. A PSE is any encoding which contains valuable information regarding a graph’s topology. Most commonly, a PSE takes the form of a matrix P ∈ ℝn×d which is either added or concatenated with a graph’s node feature matrix X in downstream architectures. At first glance, it may be hard to tell the advantage of using a PSE over a simple node embedding; why have both P and X when just X might do?

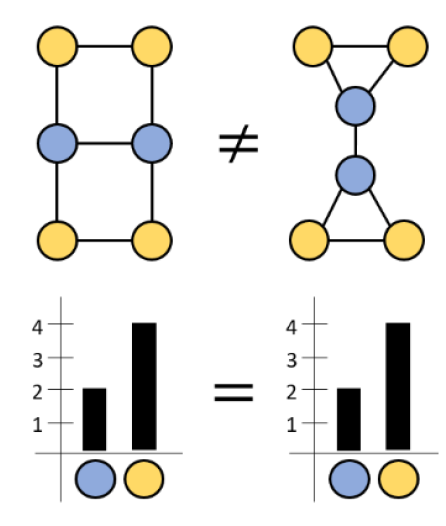

The answer is that most GNN node embedding techniques are ignorant of various graph topological features. Morris et al. [2019] and Xu et al. [2019] show that 1-hop message-passing neural networks (MPNNs), one of the most common type of GNN, are at most as powerful as the 1-dimensional Weisfeiler-Lehman (1-WL) graph isomorphism test [Weisfeiler and Lehman, 1968]. While the 1-WL test is able to distinguish various kinds of graphs, there are many graphs which it surprisingly fails to distinguish. Below, Figure 1 gives an example of a pair of indistinguishable graphs. Notice that even though the graphs are non-isomorphic, their node coloring histograms computed by the 1-WL algorithm are identical. Ideally, non-isomorphic graphs should have non-identical node color histograms.

More importantly, common substructures such as as cycles and disjointed triangles—which are common in molecular and social network data—also cannot be distinguished from each other. These structures will map to the same representations by MPNNs, harming their expressive power depending on the given dataset and task. As a result, we may make a distinction between node features, which are data and task-specific, and graph topological

Figure 1: An example from Zopf [2022] of 2 non-isomorphic graphs that the 1-WL test and MPNNs cannot distinguish.

features, which will generalize across structurally similar graphs. 1-hop MPNNs are able to create informative node features, but PSEs boost their expressive power beyond the 1-WL test by adding topological features that MPNNs would not normally be able to discover.

significant amounts of time and money, were subject to a variety of errors, and were inhibited by

The most common failure case of the 1-WL test is when nodes with statistically similar (yet non-isomorphic) neighborhoods receive the same coloring. Therefore, one approach to formulating a graph PSE is to assign a unique encoding to every node in order to distinguish all nodes in the graph. The most straightforward way to accomplish this is by augmenting each node embedding with random features [Abboud et al., 2021, Sato et al., 2021, Eliasof et al., 2023] and propagating those features via standard message-passing. However, as Wang et al. [2022] point out, random features have no guarantees for the convergence of the augmented node embeddings during training. Further, these random features may struggle to generalize to unseen graphs given that nodes in a graph have no canonical ordering. A random feature, while able to uniquely identify nodes in a graph, also says nothing about the structural role a node plays in its neighborhood. For example, nodes in a cycle should share similar PSEs versus nodes with a single neighbor. In short, a powerful graph PSE must incorporate the graph structure into its encoding and cannot just uniquely identify nodes.

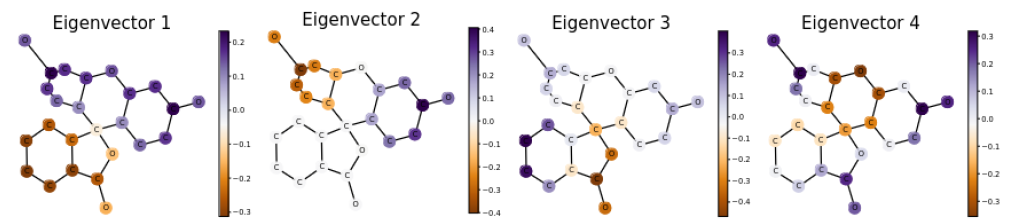

An alternative approach is to utilize the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the graph Lapla-cian matrix L, which can be intuitively thought of as the coefficients and basis functions which make up the given graph signal. Prior to the widespread use of neural networks, Belkin and Niyogi [2001] used the eigenvectors of L for graph clustering, lending to the idea that the eigenvectors of L have important information regarding the graph topology itself. To give some intuition on how the graph spectrum provides topological information, Figure 2 below shows a molecular graph’s eigenvectors as colors on the molecule itself. Each entry of a given eigenvector corresponds to a node in the graph, and the color of each node represents the magnitude of its corresponding eigenvector entry. Notice how the first eigenvector neatly splits the two halves of the molecule at the central carbon atom, and how higher-frequency eigenvectors induce finer and finer colorings.

Figure 2: Entries of various eigenvectors coloring the nodes of a molecular graph [Lim et al., 2022]. Eigenvectors are increasing in frequency from left to right.

Dwivedi and Bresson [2021] and Kreuzer et al. [2021] incorporate the Laplacian’s spec-trum directly into their neural architectures as features which are added/concatenated to the node feature matrix. While these methods take MPNNs beyond the 1-WL test and boost GNN performance on several tasks, they are largely restricted to small graphs given the com-putational cost of computing the eigendecomposition of the graph Laplacian. Furthermore, the graph Laplacian’s spectrum is only guaranteed to be real-valued if the Laplacian is sym-metric, restricting its use to undirected graphs (save for certain modifications by Furutani et al. [2019]). This makes a Laplacian-based PSE potentially unsuitable for directed graph data such as social networks. Finally, any PSE which relies on the spectrum of the graph Laplacian will have trouble distinguishing non-isomorphic co-spectral graphs: graphs which are non-isomorphic but share the same eigenvalues.

Still there are other flavors of graph PSEs. For instance, random walk-based PSEs stand between random features and Laplacian eigenvectors in terms of mathematical sophistication. Li et al. [2020] and Dwivedi et al. [2022] introduce versions of such a random walk (RW) PSE, using the relative random walk landing probabilities between nodes as positional features. Recently, Ma et al. [2023] have shown that a learned version of this RW PSE can also be used to compute shortest-path distances between nodes. This result generalizes the PSE by Ying et al. [2021] which uses the shortest path distances between nodes to bias attention scores in graph transformers, and their more general framework leads to substantial improvements in performance. Generally speaking, RW-based PSEs have been shown to be generally more efficient and performant over spectral methods. Yet, RW encodings may also incur high computational cost for large graphs due to requiring powers of the graph’s RW matrix. Furthermore, a RW PSE’s performance is intimately tied to the given graph task. For example, any task which involves heavy use of directed acyclic graphs—such as code abstract syntax trees for program analsyis or abstract meaning representations for language translation—will see less benefit from an RW encoding. This is because, in these particular graphs, random walks never return to preceding nodes, and so common strategies, such as using the self-landing probabilities during a random walk, will fail to produce discriminative features.

In sum, discovering new graph PSEs is a recent endeavor in the GNN community, and the quest for an expressive, powerful, and computationally efficient PSE continues. An ideal graph PSE would be (1) discriminative, taking a GNN beyond the 1-WL test, (2) powerful, improving performance on the tasks of interest, (3) generalizable to out-of-distribution and unseen in-distribution graph structures, and (4) computationally efficient. Random feature methods are able to satisfy (1) and (4) but not the others, while spectral and RW methods trade off (1) and (4) for mostly (2). Wang et al. [2022] and Huang et al. [2023] offer PSEs which improve on (3) by constructing provably stable encodings which respect graph sym-metries, making their PSEs more generalizable to unseen graphs. However, these methods, while theoretically satisfying, seem to not generally offer performance improvements on par with simpler spectral and RW-based PSEs. Practically speaking, then, it may be of great interest to the GNN community to investigate whether objectives (1)–(4) are actually mutu-ally achievable. One may suspect, for example, that (3) and (4) cannot be achieved jointly, but this lacks rigorous proof.

References

R. Abboud, I. I. Ceylan, M. Grohe, and T. Lukasiewicz. The surprising power of graph neural networks with random node initialization, 2021. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=L7Irrt5sMQa

M.Belkin and P. Niyogi. Laplacian eigenmaps and spectral techniques for em-bedding and clustering. In T. Dietterich, S. Becker, and Z. Ghahramani, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 14. MIT Press, 2001. URL https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2001/file/f106b7f99d2cb30c3db1c3cc0fde9ccb-Paper.pdf.

V. P. Dwivedi and X. Bresson. A generalization of transformer networks to graphs. AAAI Workshop on Deep Learning on Graphs: Methods and Applications, 2021.

V. P. Dwivedi, A. T. Luu, T. Laurent, Y. Bengio, and X. Bresson. Graph neural net-works with learnable structural and positional representations. In International Con-ference on Learning Representations, 2022. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id= wTTjnvGphYj.

M. Eliasof, F. Frasca, B. Bevilacqua, E. Treister, G. Chechik, and H. Maron. Graph posi-tional encoding via random feature propagation. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML’23. JMLR.org, 2023.

S. Furutani, T. Shibahara, M. Akiyama, K. Hato, and M. Aida. Graph signal processing or directed graphs based on the hermitian laplacian. In ECML/PKDD, 2019. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:218489847.

Y. Huang, W. Lu, J. Robinson, Y. Yang, M. Zhang, S. Jegelka, and P. Li. On the stability of expressive positional encodings for graph neural networks, 2023.

D. Kreuzer, D. Beaini, W. L. Hamilton, V. L´etourneau, and P. Tossou. Rethinking graph transformers with spectral attention. In A. Beygelzimer, Y. Dauphin, P. Liang, and J. W. Vaughan, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021. URL https: //openreview.net/forum?id=huAdB-Tj4yG.

P. Li, Y. Wang, H. Wang, and J. Leskovec. Distance encoding: Design provably more powerful neural networks for graph representation learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 2020.

D. Lim, J. D. Robinson, L. Zhao, T. Smidt, S. Sra, H. Maron, and S. Jegelka. Sign and basis invariant networks for spectral graph representation learning. In ICLR 2022 Workshop on Geometrical and Topological Representation Learning, 2022. URL https://openreview. net/forum?id=BlM64by6gc.

L. Ma, C. Lin, D. Lim, A. Romero-Soriano, K. Dokania, M. Coates, P. H.S. Torr, and S.-N. Lim. Graph Inductive Biases in Transformers without Message Passing. In International Conference on Machine. Learning., 2023.

C. Morris, M. Ritzert, M. Fey, W. L. Hamilton, J. E. Lenssen, G. Rattan, and M. Grohe. Weisfeiler and leman go neural: Higher-order graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Inno-vative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, AAAI’19/IAAI’19/EAAI’19. AAAI Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-57735-809-1. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33014602. URL https: //doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33014602.

R. Sato, M. Yamada, and H. Kashima. Random features strengthen graph neural networks.In Proceedings of the 2021 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, SDM, 2021.

H. Wang, H. Yin, M. Zhang, and P. Li. Equivariant and stable positional encoding for more powerful graph neural networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=e95i1IHcWj.

B. Weisfeiler and A. Lehman. The reduction of a graph to canonical form and the algebra which appears therein. Number 9, pages 12–16, 1968.

K. Xu, W. Hu, J. Leskovec, and S. Jegelka. How powerful are graph neural networks? In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019. URL https://openreview. net/forum?id=ryGs6iA5Km.

C. Ying, T. Cai, S. Luo, S. Zheng, G. Ke, D. He, Y. Shen, and T.-Y. Liu. Do transformers really perform badly for graph representation? In Thirty-Fifth Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=OeWooOxFwDa.

M. Zopf. 1-wl expressiveness is (almost) all you need. 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pages 1–8, 2022. URL https://api.semanticscholar. org/CorpusID:247011932.